The land

The land

La terra

La terra

Santa Maria della Giustizia lies in an area which is well-endowed with resources. Firstly, the abbey is close to one of the rare freshwater streams in the Taranto area, the Tara river, and is close to the coast, even if this has repeatedly exposed it to attacks by pirates from the sea. Over time the land, also following canalisation and reclamation, has proved to be among the most fertile in the entire municipal area. This area, located to the west of Taranto, has produced traces of cultivation and agricultural exploitation as early as the Greek age, as shown by the widespread traces of cultivation brought to light by archaeological excavations.

Morphology

Morphology

Morphology

Morphology

Santa Maria della Giustizia stands on the edge of the last escarpment of the Murgia towards the Ionian sea. Below this and up to the coast, there are scattered loose, mainly alluvial, soils formed by silts and calcarenitic gravels with diverse conglomerate forms. This type of substrate, especially in the past, was subject to recurring waterlogging phenomena, especially in the event of heavy rains. These characteristics determined the emergence of gardens and medium and small-scale farms, in which intensive horticulture was practised (hence the name Orti di Basso), mostly intended for self-consumption by the household.

The Tara river

It is one of the rare watercourses of Taranto, about 8 km to the west, which originates from a series of karst resurgences of the Ravines of Leucaspide and Gravinola, with its mouth in the Gulf of Taranto.

The river, up to 5 m wide and about 2.5 km long, has a meandering course and is up to 2 m deep.

The banks preserve large natural areas, rich in aquatic plants that host sedentary and migrating bird life.

During the eighteenth century the river was affected by the installation of cotton farming systems: this gave rise to a thriving international trade and lively textile handicrafts. This activity still partly survived in the nineteenth century, although relegated to the domestic sphere.

In the 80s of the previous century, the advent of the industrial area and of the Multipurpose Pier completely transformed the mouth of the river and the surrounding coastal landscape.

The Tara river

It is one of the rare watercourses of Taranto, about 8 km to the west, which originates from a series of karst resurgences of the Ravines of Leucaspide and Gravinola, with its mouth in the Gulf of Taranto.

The river, up to 5 m wide and about 2.5 km long, has a meandering course and is up to 2 m deep.

The banks preserve large natural areas, rich in aquatic plants that host sedentary and migrating bird life.

During the eighteenth century the river was affected by the installation of cotton farming systems: this gave rise to a thriving international trade and lively textile handicrafts. This activity still partly survived in the nineteenth century, although relegated to the domestic sphere.

In the 80s of the previous century, the advent of the industrial area and of the Multipurpose Pier completely transformed the mouth of the river and the surrounding coastal landscape.

Crops and vegetation

The soil characteristics of the land surrounding the abbey, corresponding to the Tara, Caggiuni, Paludi and Pantano districts, have allowed the early development of vegetable gardens (a feature that has also remained imprinted in medieval and modern toponymy) and of gardens, often coexisting, since the Middle Ages.

Given the marshy nature of the territory, the development of this arrangement is to be considered a conquest, obtained through grandiose agricultural reclamation works that began with the creation of a dense network of drainage channels, suitable for regulating surface water, controlling what would otherwise have been a very invasive vegetation such as Phragmites.

Throughout the 17th century, a widespread presence of moriculture is reported in the area near the abbey, which subsequently disappeared to make room for the more economically important activity of cotton growing.

Between the 17th and 18th centuries, various areas which were previously marshy or intended for grazing, following the reclamation works, were parcelled out and land concessions were granted, thus giving rise to one of the liveliest and most productive agricultural segments in the Taranto area. The abbey itself, later transformed into a farmhouse, had its own garden, the gardens of Justice, intended for the cultivation of vegetables and fruit. The vegetable gardens and gardens thus became part of a landscape dominated by olive groves, while the vineyards, although documented in the Middle Ages, were cultivated with pergolas inside the gardens in the modern age.

Pasture

The grazing of flocks is historically documented in the territory of Santa Maria della Giustizia, in particular in the historical periods prior to reclamation and to the subsequent parcelling out of the fields to private individuals to whom concessions were granted.

After all, the area is close to the route of the Regio Tratturello Tarantino, which partly follows the route of the ancient Roman Appian Way and is part of the road system traditionally used for the transhumance of flocks, regulated in Puglia since the 15th century.

The sea

The sea

The sea

The sea

The sea, a variable which is inseparable from Italian history and even more so from that of Puglia and Taranto. In this city the sea has always played a crucial role: in addition to today’s tourism, it has been crossed for centuries by commercial fleets and, thanks to the characteristics of these waters, by expert fishermen who have made its fruits famous all over the world.

Fishing

The sea of Taranto has always been generous with fish resources and free fishing has been matched by breeding. Numerous piscarìe or piscare are reported in the sources, i.e. sea lots delimited by piling raised in the waters to which there were exclusive rights following concessions. The supply of fish (salted anchovies, sea bream and mullet) for the royal table of Charles I of Anjou (1226-1285) comes from Taranto.

From the 15th century onwards, all free fishing and aquaculture activities were regulated by a complex system of rules in the Russian Book of Constitutions and Statutes for the Royal Customs of Taranto, which gave recommendations on the methods of exploitation of fish resources, on the type of catch and restrictions, besides offering interesting information on the fishing techniques which were used.

Shellfish

Among the essential sea products for the Taranto economy, shellfish have historically always represented a renowned product of the Ionian centre.

Since Roman times, Taranto has been known for oyster farming, considered a luxury food item.

Mussel farming is documented in the sources only starting from the 15th-16th century AD, when the first farms of what would become one of the excellences of the city were established.

Even the murex represented an important resource: since ancient times, purple was obtained from them, a natural dye essential to the city’s textile industry, particularly famous and appreciated also for the processing of wool and fine fabrics.

Another process, linked to textile manufacturing and documented from the 18th to the mid-20th century, was that which used byssus filaments, an organic substance produced by the Pinna Nobilis, with which refined and soft fabrics were obtained.

The salts pans

Another important resource in the Taranto economy was the production of salt, which was so famous that it is also remembered by the poet Boccaccio (1313-1375). The exploitation of the salt pans in Taranto is already documented in written sources from the Roman age, which indicate that the salt produced here was of excellent workmanship. It is speculated that the city may have played an important role in the salting and export of tuna fish caught throughout southern Italy. On the other hand, the salting systems of Taranto were also known in famous cookery treatises from the Roman era. In the 13th century the presence of an imperial monopoly on the extraction of salt is documented; some salt pans were in the hands of ecclesiastical organisations, such as monasteries, to obtain continuous supplies, in particular for the preservation of food, which is the main function for which salt was used.

Threats from the sea

Threats from the sea

Threats from the sea

Threats from the sea

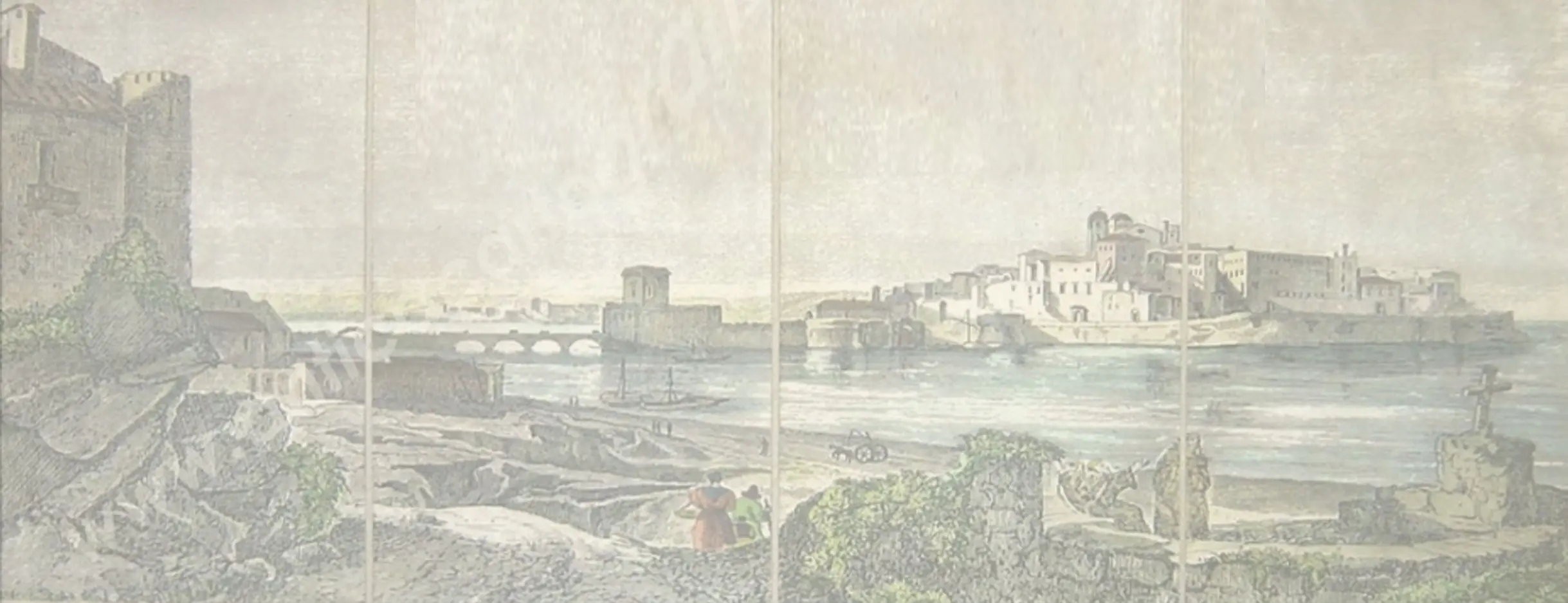

The sea could also be a harbinger of misfortune: in particular, the coast to the west of the city has suffered from recurrent pirate raids over the centuries. The abbey of Santa Maria della Giustizia itself was sacked several times by Turkish and Berber pirates from North Africa in 1520 and again in 1537, so much so that it was equipped, as early as 1521, with a real wall.

To deal with the continuous incursions, the Kingdom of Naples, between the 16th and 17th centuries, equipped itself with a defensive system consisting of watchtowers. In 1569, the towers of Capo Rondinello (also known as San Nicolicchio) and of Tara had already been erected around the abbey, but their efficiency, severely put to the test by the Turkish incursion of 1595, proved to be inadequate and the monastery was raided and set on fire.

In the upper image, a detail taken from the painting “SS. Trinity and Virgin”, 1740, by G. Mastroleo, preserved in the church of San Domenico Maggiore in Taranto; the coastal tower of Capo Rondinello is reproduced on the right.

Nell’immagine superiore, un particolare tratto dal dipinto “SS. Trinità e Vergine”, 1740, di G. Mastroleo, conservato presso la chiesa di S. Domenico Maggiore di Taranto; a destra è riprodotta la torre costiera di Capo Rondinello.